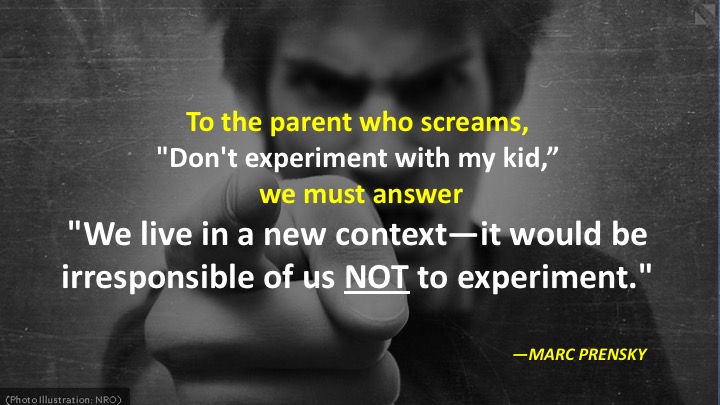

“BEYOND THE PAST” ::: HOW TO ANSWER A PARENT WHO SAYS: “DON’T EXPERIMENT WITH MY KID.”

Many parents—understandably afraid—say to (or even shout at) their children’s teachers and administrators: “Don’t experiment with my kid!” Most educators have heard some version of this from parents.

There is only one valid response:

“Sorry, but we would be acting IRRESPONSIBLY by NOT experimenting. Your kids are living in a never-before-seen context—very different from the one in which we adults grew up. The world, and your kids’ abilities in that world, are changing radically and rapidly. We do not really know as yet how to best prepare young people for that new world. But we do know that the ways of the past are no longer working and valid. So in order to be responsible educators, we have to experiment, and we can’t be afraid to. As a parent, you need to do the same, following, as best you can, your kids’ lead.

“But I just want my kid to get into college,” is the usual follow-up.

Here the response needs to be: “Yes, but your kid needs to be prepared not just for college, but what comes after. They need to be prepared for what they, uniquely, can get done and accomplish in the world. How they get to that place depends very much on who they are.